Full Metal Jacket

| Full Metal Jacket | |

|---|---|

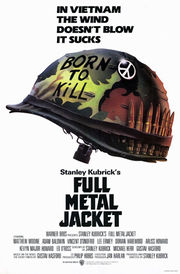

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick Jan Harlan |

| Written by | Novel: Gustav Hasford Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick Michael Herr Gustav Hasford |

| Starring | Matthew Modine Adam Baldwin Vincent D'Onofrio R. Lee Ermey |

| Music by | Vivian Kubrick |

| Cinematography | Douglas Milsome |

| Editing by | Martin Hunter |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

| Release date(s) | June 26, 1987 |

| Running time | 116 min. |

| Country | United States United Kingdom |

| Language | English Vietnamese |

| Budget | $17,000,000 (estimated) |

| Gross revenue | $46,357,676 |

Full Metal Jacket is a 1987 war film by Stanley Kubrick, based on the novel The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford. The title refers to the full metal jacket bullet used by infantry riflemen. The film follows a squad of U.S. Marines through their training and depicts some of the experiences of two of them in the Tet Offensive (1968) during the Vietnam War.

Contents |

Plot

During the Vietnam War, a group of new United States Marine Corps recruits arrives at Parris Island for recruit training. After having their heads shaved, they meet their drill instructor, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Hartman, tasked with producing battle-ready soldiers, immediately begins abusing his recruits in an attempt to harden them mentally and emotionally. The film focuses its attention on Privates 'Joker' (Matthew Modine) and 'Cowboy' (Arliss Howard), while the overweight and mentally slow Leonard Lawrence (Vincent D'Onofrio), whom Hartman nicknames "Gomer Pyle", draws the wrath of Hartman.

Unresponsive to Hartman's constant discipline, Pyle is paired with Joker. With this help, Pyle begins to improve, but progress is halted when Hartman discovers a jelly doughnut in his foot locker and Hartman punishes the entire platoon. As a result, the platoon hazes Pyle with a "blanket party," pinning him to his bunk with a blanket and beating him with bars of soap wrapped in towels. Joker reluctantly joins in and beats Pyle several times. In weeks following the beating, Pyle undergoes a transformation, becoming a model Marine and an expert rifleman, but he shows signs of mental breakdown - including social withdrawal and talking to his rifle.

After graduation, the Corps assigns each recruit to an occupational specialty, most being assigned to the infantry, though Joker is assigned to Basic Military Journalism. On the platoon's last night on Parris Island, Joker is assigned to fire watch, during which he discovers Pyle in the head loading his rifle with live ammunition. Joker attempts to calm Pyle, who begins shouting, executing drill commands, and reciting the Rifleman's Creed. The noise awakens Hartman, who confronts Pyle. Pyle murders Hartman, then commits suicide.

The film flashes forward to January 1968, with Joker having become a sergeant and a Marine Combat Correspondent in Vietnam with Stars and Stripes, assigned to a public-affairs unit along with Private First Class Rafter Man (Kevyn Major Howard), a combat photographer. Rafter Man wants to go into combat, as Joker claims he has done, though one of his colleagues mocks Joker's inexperience, claiming he doesn't have the thousand-yard stare. The sound of nearby gunfire interrupts their argument: the North Vietnamese Army has begun the Tet Offensive and attempts to overrun the base.

The journalism staff is briefed the next day about enemy attacks throughout South Vietnam. Joker's commander, Lt. Lockhart, sends Joker to Phu Bai, a Marine forward operating-base near Huế. Rafter Man accompanies him to get combat experience. There, they meet the Lusthog Squad, where Cowboy is now a Sergeant and second-in-command. Joker accompanies the squad during the Battle of Huế, during which the enemy kills their commander, Lt. Touchdown (Ed O'Ross).

During a patrol north of the Perfume River, the squad leader is killed, leaving Cowboy in command. The squad becomes lost in the rubble, where a sniper pins them down and wounds two of them. The sniper refrains from killing the wounded men with the intention of drawing more of the squad into the killing zone. As the squad maneuvers to locate the hidden position, Cowboy is shot and killed.

With Cowboy dead, the squad's machine gunner, Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), assumes command of the survivors. Under the cover of smoke grenades, the squad advances on the sniper's position where Joker locates the enemy soldier on an upper floor. His rifle jams as he tries to shoot. The sniper is revealed to be a young girl, and is shot by Rafter Man. As Animal Mother and other Marines of the squad converge, she begins to pray then repeatedly begs for death, prompting an argument about whether or not to kill her. Animal Mother decides to allow a mercy killing only if Joker performs it. After some hesitation, Joker shoots her with his sidearm. The Marines congratulate him on his kill as Joker stares into the distance. The film concludes with the Marines marching toward their bivouac, singing the Mickey Mouse March. Joker states that despite being "in a world of shit" that he is glad to be alive, and is unafraid.

Cast and characters

- Matthew Modine as Private/Sergeant James T. "Joker" Davis, the protagonist-narrator who claims to have joined the Corps to see combat, and to become the first one on his block with a confirmed kill. He witnesses Pyle's insanity in boot camp, but nevertheless becomes a "squared away" Marine. He later serves as an independently-minded combat correspondent accompanying the Lusthog Squad in the field. Joker wears a peace-sign medallion on his uniform as well as writing "Born to Kill" on his helmet.

- Vincent D'Onofrio as Private Leonard "Gomer Pyle" Lawrence: An overweight, clumsy, slow-witted recruit who becomes the focus of Hartman's attention for his incompetence and excess weight, making him the platoon scapegoat. After a blanket party from the rest of the platoon for failing almost everything and earning them collective punishments, he turns psychotic and talks to his rifle, "Charlene." He later shoots and kills D.I. Hartman while in the bathroom and then himself in front of Joker. The humiliating nickname Gomer Pyle originates from a likable but dim character from the American television program The Andy Griffith Show who eventually enlists in the USMC.

- R. Lee Ermey (credited as "Lee Ermey") as Gunnery Sergeant Hartman: the archetypal Parris Island drill instructor who trains his recruits to transform them into Marines. R. Lee Ermey actually served as a U.S. Marine Drill Instructor during the Vietnam War. Based on this experience he ad-libbed much of his dialog in the movie.

- Arliss Howard as the Texan Private / Sergeant "Cowboy" Evans who goes through boot camp with Joker. He becomes a rifleman and later encounters Joker in Vietnam, taking command of a rifle squad. In Full Metal Jacket, he quickly dies of a sucking chest wound, while in Joker's arms and weakly saying "I can hack it...", surrounded by the few remaining members of his squad.

- Adam Baldwin as Sergeant "Animal Mother": the nihilistic M-60 machine gunner of the Lusthog Squad, Animal Mother scorns any authority but his own, and attempts to rule by intimidation. Animal Mother believes in victory as the only object of war.

- Dorian Harewood as Corporal "Eightball": The African-American member of the Lusthog Squad, insensitive about his ethnicity (e.g. 'Put a nigger behind the trigger'), and Animal Mother's closest friend. The sniper shoots him repeatedly in an attempt to lure the others into the open, before killing him.

- Kevyn Major Howard as Private First Class "Rafter Man": Rafter Man works as a combat photographer in the Stars and Stripes office with Joker. He requests permission to accompany Joker into Huế and ultimately saves him by shooting the sniper, an act which gives him much pride and exhilaration.

- Ed O'Ross as Lieutenant Walter J. "Touchdown" Schinowski: The commander of the Lusthog Squad's platoon, he was a college football player at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana. He is killed in an ambush outside of Huế City.

- John Terry as Lieutenant Lockhart: The PAO Officer in Charge and Joker's assignment editor. He has combat-reporting experience, but uses his officer rank to avoid returning to the field, he says on account of the danger and the bugs, rationalizing that his journalistic duties keep him where he belongs, "In the rear with the gear."

- Kieron Jecchinis as Sergeant "Crazy Earl": The squad leader, he is forced to assume platoon command when Platoon Leader Lt. Touchdown is killed. Touching a booby-trapped toy kills him. As in the novel he carries a BB gun, which is visible just before he dies.

- John Stafford as Doc Jay: A Navy corpsman attached to the Lusthog squad. Doc Jay mocks President Johnson when he is interviewed by documentary men in the film, Doc Jay quotes LBJ when he was Vice President expressing his intentions to avoid sending American soldiers to Vietnam. He is wounded by the sniper while attempting to drag Eightball to safety; the sniper uses a subsequent automatic burst to finish them both off when Doc Jay attempts to indicate the direction of the sniper.

- Tim Colceri as the door gunner, the Loadmaster and machine gunner of the H-34 Choctaw helicopter transporting Joker and Rafter Man to the Tet Offensive front. Inflight, he shoots at civilians, while enthusiastically repeating "Get some!", boasting "157 dead Gooks killed, and 50 water buffaloes too." When Joker asks if that includes women and children, he admits it stating, "Sometimes." Joker then asks, "How could you shoot women and children?" to which the door-gunner replies jokingly, "Easy, you just don't lead 'em so much!...Ha, ha, ha, ha...Ain't war hell?!" This scene is adapted from Michael Herr's 1977 book Dispatches.

- Papillon Soo Soo as Da Nang Hooker: An attractive and scantily-dressed prostitute who approaches Joker and Rafter Man at a street corner during the first scene in Vietnam. She is memorable for the phrases "Me love you long time", "Me so horny" and "Me sucky sucky", which were later sampled by 2 Live Crew in their song, "Me So Horny" and in Sir Mix-a-Lot's "Baby Got Back".

- Peter Edmund as Private "Snowball" Brown: African-American recruit, the butt of jibes from Hartman about "fried chicken and watermelon", and famous for informing him that Lee Harvey Oswald shot Kennedy from "that book suppository [sic] building, Sir!". He doesn't appear in Vietnam.

Production

Development

Stanley Kubrick contacted Michael Herr, author of the Vietnam War memoir Dispatches, in the spring of 1980 to discuss working on a film about the Holocaust but eventually discarded that in favor of a film about the Vietnam War.[1] They met in England and the director told him that he wanted to do a war film but he had yet to find a story to adapt.[2] Kubrick discovered Gustav Hasford's novel The Short-Timers while reading the Virginia Kirkus Review[3] and Herr received it in bound galleys and thought that it was a masterpiece.[2] In 1982, Kubrick read the novel twice and afterwards thought that it "was a unique, absolutely wonderful book" and decided, along with Herr,[1] that it would be the basis for his next film.[3] According to the filmmaker, he was drawn to the book's dialogue that was "almost poetic in its carved-out, stark quality."[3] In 1983, he began researching for this film, watching past footage and documentaries, reading Vietnamese newspapers on microfilm from the Library of Congress, and studied hundreds of photographs from the era.[4] Initially, Herr was not interested in revisiting his Vietnam War experiences and Kubrick spent three years persuading him in what the author describes as "a single phone call lasting three years, with interruptions."[1]

In 1985, Kubrick contacted Hasford to work on the screenplay with him and Herr,[2] often talking to Hasford on the phone three to four times a week for hours at a time.[5] Kubrick had already written a detailed treatment.[2] The two men got together at Kubrick's home every day, breaking down the treatment into scenes. From that, Herr wrote the first draft.[2] The filmmaker was worried that the title of the book would be misread by audiences as referring to people who only did half a day's work and changed it to Full Metal Jacket after discovering the phrase while going through a gun catalogue.[2] After the first draft was completed, Kubrick would phone in his orders and Hasford and Herr would mail in their submissions.[6] Kubrick would read and then edit them with the process starting over. Neither Hasford nor Herr knew how much they contributed to the screenplay and this led to a dispute over the final credits.[6] Hasford remembers, "We were like guys on an assembly line in the car factory. I was putting on one widget and Michael was putting on another widget and Stanley was the only one who knew that this was going to end up being a car."[6] Herr says that the director was not interested in making an anti-war film but that "he wanted to show what war is like."[1]

At some point, Kubrick wanted to meet Hasford in person but Herr advised against this, describing The Short-Timers author as a "scary man."[1] Kubrick insisted and they all met at Kubrick's house in England for dinner. It did not go well and Hasford was subsequently shut out of the production.[1]

Casting

Through Warner Bros., Kubrick advertised a national search in the United States and Canada.[2] The director used video tape to audition actors. He received over 3,000 video tapes.[2] His staff screened all of the tapes and eliminated the unacceptable ones. This left 800 tapes for Kubrick to personally review.[2]

Former U.S. Marine Drill Instructor R. Lee Ermey was originally hired as a technical adviser and asked Kubrick if he could audition for the role of Hartman. However Kubrick, having seen his portrayal as Drill Instructor SSgt Loyce in The Boys in Company C, told him that he wasn't vicious enough to play the character.[2] In response, Ermey made a videotape of himself improvising insulting dialogue towards a group of Royal Marines while people off-camera pelted him with oranges and tennis balls. Ermey, in spite of the distractions, rattled off an unbroken string of insults for 15 minutes, and he did not flinch, duck, or repeat himself while the projectiles rained on him.[2] Upon viewing the video, Kubrick gave Ermey the role, realizing that he "was a genius for this part".[4] Ermey's experience as a real-life DI during the Vietnam era proved invaluable, and he fostered such realism that in one instance, Ermey barked an order off-camera to Kubrick to stand up when he was spoken to, and Kubrick instinctively obeyed, standing at attention before realizing what had happened. Kubrick estimated that Ermey came up with 150 pages of insults, many of them improvised on the spot — a rarity for a Kubrick film. According to Kubrick's estimate, the former drill instructor wrote 50% of his own dialogue, especially the insults.[7] Ermey usually needed only two to three takes per scene, another rarity for a Kubrick film.

The original plan envisaged Anthony Michael Hall starring as Private Joker, but after eight months of negotiations a deal between Stanley Kubrick and Hall fell through.[8]

Kubrick offered Bruce Willis a role, but Willis had to turn down the opportunity because of the impending start of filming on the first 6 episodes of Moonlighting.[9]

Principal photography

Kubrick shot the film in England: in Cambridgeshire, on the Norfolk Broads, and at the former Beckton Gas Works, Newham (east London). A former RAF and then British Army base, Bassingbourn Barracks, doubled as the Parris Island Marine boot camp.[4] A British Army rifle range near Barton, outside Cambridge was used in the scene where Private Pyle is congratulated on his shooting skills by R. Lee Ermey. The disused Beckton Gasworks portrayed the ruined city of Huế. Kubrick worked from still photographs of Huế taken in 1968 and found an area owned by British Gas that closely resembled it and was scheduled to be demolished.[7] To achieve this look, Kubrick had buildings blown up and the film's art director used a wrecking ball to knock specific holes in certain buildings over the course of two months.[7] Originally, Kubrick had a plastic replica jungle flown in from California but once he looked at it was reported to have said, "I don't like it. Get rid of it."[10] The open country is Cliffe marshes, also on the Thames, with 200 imported Spanish palm trees[3] and 100,000 plastic tropical plants from Hong Kong.[7]

Kubrick acquired four M41 tanks from a Belgian army colonel (a fan), Sikorsky H-34 Choctaw helicopters (actually Westland Wessex painted Marine green), and obtained a selection of rifles, M79 grenade launchers and M60 machine guns from a licensed weapons dealer.[4]

Matthew Modine described the shoot as tough: he had to have his head shaved once a week and Ermey yelled at him for ten hours a day during the shooting of the Parris Island scenes.[11]

At one point during filming, Ermey had a car accident, broke all of his ribs on one side and was out for four-and-half months.[7] Cowboy's death scene shows a building in the background that resembles the famous alien monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick described the resemblance as an "extraordinary accident."[7]

During filming, Hasford contemplated legal action over the writing credit. Originally the film-makers intended Hasford to receive an "additional dialogue" credit, but he wanted full credit.[6] The writer took two friends and sneaked onto the set dressed as extras only to be mistaken by a crew member for Herr.[5]

Kubrick's daughter Vivian - who appears uncredited as news-camera operator at the mass grave - shadowed the filming of Full Metal Jacket and shot eighteen hours of behind-the-scenes footage, snippets of which can be seen in the 2008 documentary Stanley Kubrick's Boxes.

Music

"Abigail Mead" (an alias for Kubrick's daughter Vivian) wrote a score for the film. According to an interview which appeared in the January 1988 issue of Keyboard Magazine, the film was scored mostly with a Fairlight CMI synthesizer (the then-current Series III edition), and the Synclavier. For the period music, Kubrick went through Billboard's list of Top 100 Hits for each year from 1962–1968 and tried many songs but "sometimes the dynamic range of the music was too great, and we couldn't work in dialogue."[7]

- Johnnie Wright - "Hello Vietnam"

- The Dixie Cups - "Chapel of Love"

- Sam the Sham & The Pharaohs - "Wooly Bully"

- Chris Kenner - "I Like It Like That"

- Nancy Sinatra - "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'"

- The Trashmen - "Surfin' Bird"

- Goldman Band - "Marines' Hymn"

- The Rolling Stones - "Paint It Black" (End Credits)

Reception

Full Metal Jacket received critical acclaim. Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader labeled it "the most tightly crafted Kubrick film since Dr. Strangelove". [12] Variety referred to the film as an "intense, schematic, superbly made" drama, while Vincent Canby of the New York Times called it "harrowing" and "beautiful." Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert had a dissenting view, stating the film was "strangely shapeless", giving it a a 2.5 stars - a "thumbs down" by Ebert's standards.[13]Gene Siskel famously took Ebert to task for this view on their television show, especially so for simultaneously praising Benji the Hunted. Rotten Tomatoes gives the movie a 96% rating.[14][15]

The film received a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Writing for an adapted screenplay. Ermey was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor.

Full Metal Jacket ranks 457th on Empire's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[16]

In March 2008, the film became the first to receive a double-dipping on Blu-ray Disc.[17]

Interpretation

Compared to Kubrick's other works, the themes of Full Metal Jacket have received little attention from critics and reviewers. With the exception of Rob Ager's lengthy video narration, The Hidden Hand,[18] reviews have mostly focused on military brainwashing themes in the boot-camp training section of the film, while seeing the latter half of the film as more confusing and disjointed in content. Rita Kempley of the Washington Post wrote, "it's as if they borrowed bits of every war movie to make this eclectic finale."[19] Roger Ebert explained, "The movie disintegrates into a series of self-contained set pieces, none of them quite satisfying."[20] Ager interprets these aspects of the film as Kubrick's satirical critique of pro-war propaganda in Hollywood war movies.

Accolades

- Nomination - Best Adapted Screenplay (Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr, Gustav Hasford)

Awards of the Japanese Academy

- Nomination - Best Foreign Language Film (Stanley Kubrick)

BAFTA Awards

- Nomination - Best Sound (Nigel Galt, Edward Tise, Andy Nelson)

- Nomination - Best Special Effects (John Evans)

Boston Society of Film Critics Awards

- Won - Best Director (Stanley Kubrick)

- Won - Best Supporting Actor (R. Lee Ermey)

David di Donatello Awards

- Won - Best Producer - Foreign Film (Stanley Kubrick)

- Nomination - Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture (R. Lee Ermey)

Kinema Junpo Awards

- Won - Best Foreign Language Film Director (Stanley Kubrick)

London Critics Circle Film Awards

- Won - Director of the Year (Stanley Kubrick)

Writers Guild of America

- Nomination - Best Adapted Screenplay (Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr, Gustav Hasford)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 CVulliamy, Ed (July 16, 2000). "It Ain't Over Till It's Over". The Observer. http://books.guardian.co.uk/departments/artsandentertainment/story/0,6000,343722,00.html. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 LoBrutto, Vincent (1997). "Stanley Kubrick". Donald I. Fine Books.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Clines, Francis X (June 21, 1987). "Stanley Kubrick's Vietnam". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/library/film/062187kubrick-jacket.html. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Rose, Lloyd (June 28, 1987). "Stanley Kubrick, At a Distance". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/movies/features/kubrick1987.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lewis, Grover (June 28, 1987). "The Several Battles of Gustav Hasford". Los Angeles Times Magazine. http://www.gustavhasford.com/battles.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Carlton, Bob (1987). "Alabama Native wrote the book on Vietnam Film". Birmingham News. http://www.gustavhasford.com/interview.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Cahill, Tim (1987). "The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0077.html. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Epstein, Dan. "Anthony Michael Hall from The Dead Zone - Interview". Underground Online. http://www.ugo.com/channels/filmtv/features/anthonymichaelhall/. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ "BRUCE WILLIS: PLAYBOY INTERVIEW". playboy.com. Playboy.com. http://www.playboy.com/articles/playboy-interview-bruce-willis/index.html?page=2. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ↑ Watson, Ian (2000). "Plumbing Stanley Kubrick". Playboy. http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0094.html. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Linfield, Susan (October 1987). "The Gospel According to Matthew". American Film. http://www.gustavhasford.com/interview-modine.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/fullmetaljacket/ - Full Metal Jacket reviews at Metacritic.com

- ↑ Ebert, Roger. "Full Metal Jacket". rogerebert.com. rogerebert.com. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19870626/REVIEWS/706260302/1023. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "The Undeclared War Over Full Metal Jacket". Thedailybeast.com. RTST, INC. http://www.thedailybeast.com/blogs-and-stories/2010-03-26/seven-classic-at-the-movies-moments/full/. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". rottentomatoes.com. Muze Inc.. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/full_metal_jacket. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". http://www.empireonline.com. Bauer Consumer Media.. http://www.empireonline.com/500/8.asp. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "Full Metal Jacket: Special Edition". hmv.com. hmv 2010. http://hmv.com/hmvweb/displayProductDetails.do?ctx=280;0;-1;-1;-1&sku=745410. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ↑ The Hidden Hand, video analysis of Full Metal Jacket http://www.collativelearning.com/FMJ%20contents.html

- ↑ Washington Post Review http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/fullmetaljacketrkempley_a0ca77.htm

- ↑ Roger Ebert Review http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19870626/REVIEWS/706260302/1023|accessdate=22 July 2010

- ↑ "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". nytimes.com. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/18878/Full-Metal-Jacket/awards. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

External links

- Full Metal Jacket at the Internet Movie Database

- Full Metal Jacket at Allmovie

- Full Metal Jacket script at the Internet Movie Script Database

- Full Metal Jacket at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford - original text

|

|||||||||||||||||